Are the struggles against racism in Britain and the USA different? What is the relationship between race, class and national identity? APRIL ASHLEY, a female Black members’ representative on the national executive council of public sector union Unison, reviews in a personal capacity a recent book that raises these issues.

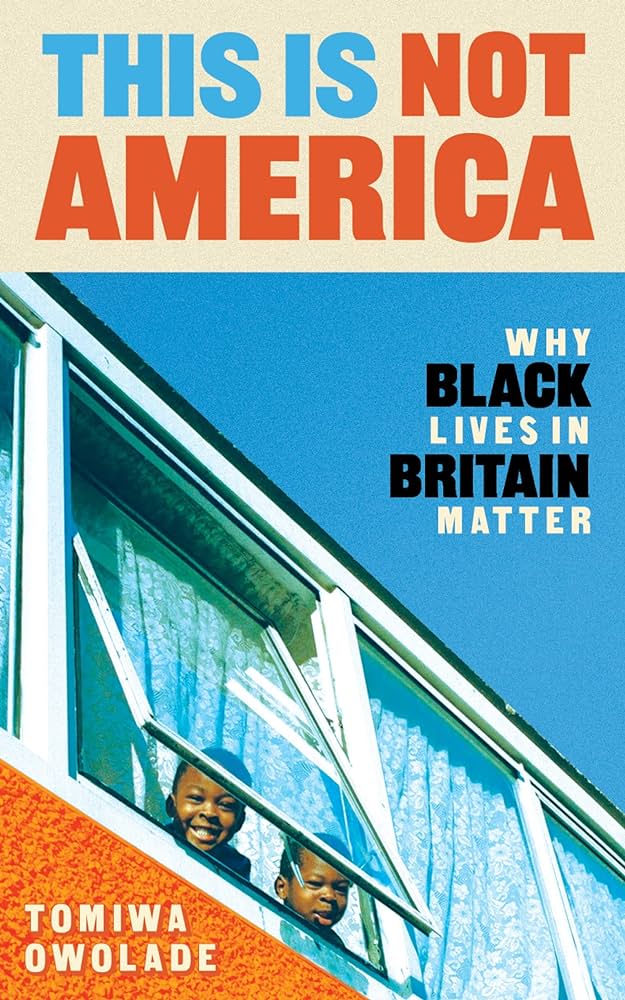

This Is Not America – Why Black Lives in Britain Matter

By Tomiwa Owolade

Published by Atlantic Books, 2023, £9.49

Following the explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement after the racist murder of George Floyd in 2020, this book by Tomiwa Owolade, a Nigerian-born British writer, is an easy and interesting read, discussing the different experience of racism in America and Britain

Owolade argues that although all Black people suffer from racism there is a difference being Black American and Black British because of the differences in history and culture. And although, ostensibly, a simple argument, Owolade sets out to explore exactly what this means.

He begins by looking at the overall experience of racism suffered by Black people in Western society, but concentrating on the experiences of Black American and Black British communities. He cites demographic differences such as the fact that the Black American population is up to 19% of the general American population and can trace its ancestry to slavery whilst the Black British population is only 4% and largely immigrants or children of immigrants. Racial segregation has been a major feature in US society whilst not so much in Britain.

Many of his arguments are not new, and he concludes that we shouldn’t follow the USA road in fighting racism as it is not as bad in the UK. “More recently, despite the discrimination in housing, employment, criminal justice, and education that many Black people faced in Britain after the second world war, there was no equivalent in British laws of the Jim Crow segregation (between the late nineteenth century and the mid-1960s) that was enshrined in America. Lynching has never been practised in the United Kingdom. Interracial marriage has never been banned in Britain. Our schools are not segregated by race, but by class”.

However, many Black youth and workers in Britain may not be convinced by this argument. On the Black Lives Matter protests we saw many calling out racism in the UK, holding up placards stating ‘the UK is not innocent’, pointing out the inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic – with Black workers four times more likely to die than white workers – as well as the killing of Black people in police custody. Whether looking at the statistics for unemployment, wages, housing or health, Black workers are disproportionately worse off.

Critical Race Theory

Owolade critiques the American concept of ‘Critical Race Theory’ (CRT) expounded by Black American intellectuals who argue that “Racism is not a blemish on the country. It is an integral part of America”; that it is a permanent feature of American life and in existential conflict with its Black citizens.

Although Owolade quotes Stokley Carmichael – leader of the Black Power Movement in the 1960s – that “the enduring presence of capitalism is why there is no progress for Black people in America”,he nevertheless criticises the fact that, unlike traditional civil rights movements, which embrace incrementalism and step-by-step progress, Critical Race Theory questions the very foundations of the ‘liberal order’.

Socialists, on the other hand, would agree with the idea that racism cannot be defeated incrementally in the current society. There have been some legal improvements and progress – and it’s important to fight for every reform that can be won – but racism has not been fundamentally defeated.

However, what exactly is the ‘liberal order’? And what should be put in its place? Here the Critical Race Theorists have no solutions. Socialists would agree with Malcolm X that racism is built into the foundations of capitalism in America – although, at the time of his death, he had not himself drawn the conclusion that capitalism needed to be overthrown by the organised working class and replaced by socialism in order for racism to be eliminated.

Owolade rightly criticises the Critical Race Theorists’ individualist approach to combating racism that consists of white individuals admitting and personally undoing their racism as a self-help process instead of a collective political process challenging power. And although their theory talks about ‘power’ it is vague on how to combat the power imbalance and sees everything in the light of race. Owolade says that while there is intersectionality in the theory, at the bottom is race and white supremacy. Class is rarely mentioned.

National identity and class

Owolade writes that in Britain immigration is a significant factor in shaping racism and recounts the experience of the Windrush generation. He describes the betrayal of the labour and trade union movement of the Caribbean and Asian migrants and notes Harold Wilson’s government’s tightening of immigration controls, especially of the Kenyan Asians, in 1968.

However, he argues that integration of the Windrush generation into British society has firmly establish a British identity amongst Black people: “Black British people are a part of Britian; this affinity is sometimes made invisible by the tragic reality of racism. But it nevertheless remains true. And any form of anti-racist politics needs to insist on it”.

In writing about what it means to be Black and British Owolade talks of ‘Double Consciousness’, arguing that Black people are comfortable with the British nation. He is critical of identity politics as being defined just by your race as reductive but is very much in favour of being defined by your nationality.

In his discussion on the British Empire, although criticising its brutality, he compares it favourably to the empires of other European nations. This seems to be excusing British colonialism in order for him to embrace the British nation state.

Owolade states that in Britain class plays a much clearer dividing line in Britain compared to America. It is true that discussions around class have been sharper in the UK because of the relative strength of the labour and trade union movement and the allegiance to it of the majority of Black workers. Trades Union Congress’ statistics show that Black workers account for just 3.4% of all employees but 3.8% of union members. A 2022 survey found that 29% of Black workers are in a trade union compared to 23.3% of white workers.

But Owolade seeks to go further, dividing the Black community into more specific communities – African, Caribbean, Chinese and Indian – in order to define and combat racial discrimination, arguing that there are key differences between racial and ethnic groups, which he puts down not only to class but to culture. So Black Africans are doing well in Britain compared to Caribbean workers and Black African students have a higher education attainment than their Black Caribbean counterparts. But in arguing that Black communities in London are pulling away in education from the rest of Britain, he doesn’t mention that funding of education in London, although inadequate, has been higher than many other parts of the country.

Undoubtedly some differences do exist. As he points out, Black Caribbean people came to Britain as working-class labourers whilst Black Africans often come as students. There is a useful discussion on why some Black workers find difficulty in using the term BAME, as communities may feel that their cultures and backgrounds are being marginalised. He also notes strains between some African and Caribbean communities.

But his approach nonetheless risks elevating ‘cultural’ divisions and obscuring the importance of class as a potential unifying factor for Black workers and the need for a collective struggle by workers’ organisations against racism and the capitalist system that gave rise to and perpetuates it.

He does admit that class plays a significant part in the worse social conditions of Black youth, referring to “the unique difficulties faced by many poor working-class pupils of all racial backgrounds. Some of these difficulties include not just lack of funds, but also lack of social capital: their families don’t have the personal connections that wealthier families have, which can prove valuable in getting their child a job. There is also the lack of cultural capital; they don’t possess the books and musical instruments at home that can nourish a child’s knowledge and improve his or her chances at school”.

Owolade also argues that class is the key to understanding inequality in Britain when it comes to work, and cites a study by KPMG (an international accountancy firm) from December 2022 that found that social class is the biggest barrier to career progression in the UK.

He does not make the same observation for America. However, class exploitation for Black workers also exists in America and there is just as much need to link the fight against racism to the fight against class exploitation and the capitalist system in both countries.

But in order to combat racism Owolade makes a plea not for systemic change but for further integration into British life. For example, he looks at football and the fact that a large portion of the English football team, like Marcus Rashford and Bukayo Saka are Black, and even before them there were John Barnes, Ian Wright, Ashley Cole etc.

He notes that African Christian churches are sustaining Christianity in London and Grime music is part of British youth culture.

He also notes the progressive changing social attitudes towards integration. “In 1983 more than 50 per cent of British people would not marry someone from a different race. By 2020 more than 90 per cent would accept their child marrying someone from a different race. Nearly 80 per cent of the respondents believed it was important too for immigrants to integrate into society and this figure was the highest for Black people and those born outside the UK”.

Therefore, his conclusion to combat racial discrimination is for Black people to integrate further into British society, build a better relationship between the police and the Black community, and to focus specifically on cultural differences to improve educational outcomes for Black youth.

He does concede that we need to improve the material conditions for Black workers but there is no discussion on how this could be done.

He seems to conclude that under a fairer capitalist system we can overcome racism. Although he doesn’t advocate an individual way to fight racism, he doesn’t challenge the power of the capitalist elites in society.

As socialists we would disagree with Owolade’s conclusion and echo Malcolm X that “you can’t have capitalism without racism” – that capitalism is the basis of racism, discrimination and exploitation, and only a united working class has the potential to change society and fight for socialism to end them.